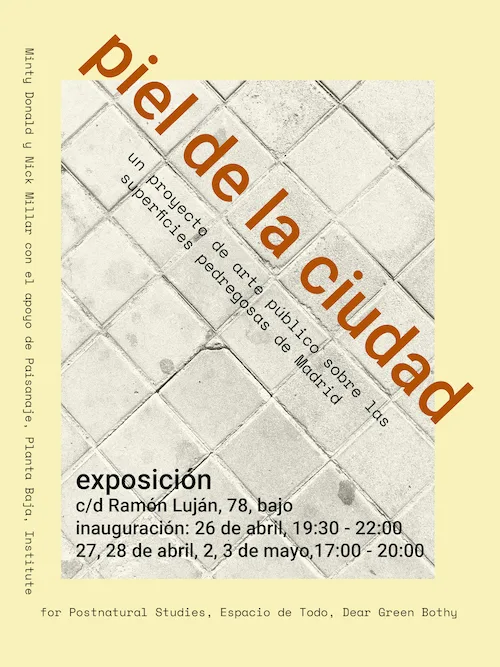

Artists Minty Donald and Nick Millar of Erratic Drift answer the question, “What is Madrid made of?” in this special guest post written ahead of their exhibition opening.

A close look at the city

When we visit a city as tourists, we’re often urged to stand back and look up to appreciate the architecture, or to seek out elevated viewpoints where we can see the city as a panorama, or understand the patterns of its streets, squares, and parks laid out before us. But what if we were to shift our gaze and zoom in on the textures and surfaces of a city’s ‘skin’? What might we discover about a city through taking a more microscopic view? What if we focused on the materials that make a city, like stone, bricks, paving stones, and concrete?

We are artists who split our time between Glasgow, Scotland, and Madrid. In our current project, Piel de la Ciudad (Skin of the City), we are taking a close-up view of the stony materials of Madrid. Throughout spring 2024, we’ve been walking the streets of four barrios: Carabanchel, Ciudad Lineal, Usera, and Vallecas. We’ve been paying close attention to pavements, roads, kerbs and walls; and to the rocky substances that they are made of: bricks, limestone, granite, and concrete. We’ve been helped in our research by the generosity of local people and experts. We’ve been trying to get to know the city better by focusing on its stony ‘skin’ and, at times, we’ve also been finding out a little about what is under that skin.

Granite and limestone

We’ve learned that granite, which is used widely in Madrid, was first quarried in quantity near the Sierra de Guadarrama in the 16th and 17th centuries. This granite goes by the local name of Berroqueña stone. On a clear day, standing in San Isidro Park in Carabanchel (perhaps with granite cobblestones underfoot) or in other high points of the city, you can see the mountain range where this hard, durable rock was pushed upwards by tectonic forces to form the Sierra (mountain-range), 20 million years ago.

You can recognise Berroqueña granite by its distinctive dark patches. We think that these patches look a little like moles or birthmarks on the skin of the city, but other people have told us they mistook them for discarded chewing gum! The marks are called ‘gabarros’ by quarrymen and ‘xenolitos’ by geologists. They are pockets of a different type of mineral, which was trapped as the granite formed.

We’ve learned that the hardest, most sought-after, limestone in Madrid is called Colmenar stone (named after Colmenar de Oreja where it was quarried). It can be polished smooth to look almost like marble. The Colmenar quarry is now spent, and this type of limestone has become a scarce commodity. Limestone, which is younger than granite (in geological terms) is formed from the compressed bones and shells of sea creatures. Colmenar stone dates from the epoch when the area where Madrid now stands was submerged under a large lake. Sometimes, if you look closely, you can see tiny, fossilised shells in limestone walls.

Bricks and mortar

We’ve found out a lot about bricks. The geology of many parts of Madrid provided perfect conditions for making bricks (and roof tiles): clay and sand. Looking at old maps, we have identified many brick and tile factories in Carabanchel, Las Ventas (where bricks for the Plaza de Toros were made) and other parts of the city. We have read that before the sizing of bricks was regulated, parts of the human body were used as standards: the foot, palm of the hand, and fingers were taken to measure the length, breadth, and depth of a brick. Someone also told us that roof tiles were made by placing wet clay over a human thigh, giving the tiles their distinctive curved shape. We’ve also noticed several different patterns of bricklaying and have learned that they go by different names: ‘Inglés’, ‘Español’, ‘Flamenco’ and ‘Holandes’.

Urban heat island effect

We’ve also become slightly obsessed by the ordinary and ubiquitous ‘baldosas de Madrid’. The baldosas are the square, concrete paving tiles that cover so many of Madrid’s streets. These tiles, measuring 15 cm x 15 cm, were first introduced in the 1950s and are, we believe, unique to Madrid. At first, they may appear uniform and monotonous, but when you look closely you notice variations where the tiles have become pitted or worn, where a strip of tiles has been replaced following underground works, or where a tree root has buckled and split the baldosas. The baldosas, however, are just one of the many types of cement and concrete that form the stony fabric of Madrid.

We’ve noticed just how much cement there is in the city! This gives us pause for thought, in the context of climate change. The cement industry is responsible for seven per cent of CO2 emissions in the world. Cement also contributes to other problems. Cement, concrete and other hard, non-porous substances trap heat, making the city hotter in summer. They can exacerbate the effects of flooding, and they make inhospitable habitats for insects, plants and animals, limiting biodiversity.

The skin of the city

Another common feature of Madrid’s stony ‘skin’ is the hard-packed sand and clay, dotted with fragments of brick, tiles and stones, found in many of the city’s parks. We have learned that much of this material is rubble (escombros) from demolished houses, which was used to fill in river valleys and level parts of the city during the rapid urbanisation of the 60s and 70s. In some parts of the city, such as La Concepción, the rubble came from ‘unofficial houses’ which had been built outside the boundaries of the city (around the same time the city’s chabolas or shanty towns were constructed). The ‘unofficial houses’ had to be constructed very quickly, often overnight, to evade the law. They were known as Flores de la Luna (Flowers of the Moon).

As we walk the city’s streets, we have been collecting fragments of stony material that have detached themselves from the surfaces of streets, roads, parks, and buildings: small pieces of the city that have chipped or peeled from its skin. It’s prompted us to re-think some of our preconceptions of stone-built cities as solid and enduring. If you look closely, you will see that the stony skin of the city is always changing, always on the move.

Minty Donald and Nick Millar are Madrid and Glasgow-based artists whose practice includes performance, writing, and sculptural installation. Their joint project Erratic Drift examines the intersections between architecture and geology. Piel de la Ciudad is an exhibition about the stony ‘skin’ of Madrid. The exhibition opens at C/d Ramón Luján 78, Usera on 26 April, between 19:30 and 22:00 and continues 27, 28 April, 2, 3 May 17:00 – 20:00.