Ayuso squares off against Ateneo

Ateneo de Madrid, one of the city’s most important cultural institutions, has just had its 100,000 euros per annum local government funding abruptly shut off. The only local organization hit by a total funding cut, speculation that the move is politically motivated is rife. The heart of the problem seems to be the simmering animosity between the president of Ateneo, Luis Arroyo Martínez, and the president of the Comunidad de Madrid, Isabel Ayuso. An article in El Confidencial claims Arroyo has been accused of badmouthing the President of the Comunidad and that in turn, Ayuso has refused numerous invites to events held at the institution. As allegations of anti-intellectualism begin to fly from the hallowed gates of Ateneo de Madrid, it’s a good moment to take a look at the history of this institution and the role it’s played in Spain’s intellectual life.

Ateneo de Madrid’s stormy origins

Since its very inception, Ateneo has been caught up in political storms. The cultural society was formed in the early 19th century, a tumultuous time when Spain struggled for intellectual freedom. Founded in 1820 during a brief respite from Ferdinand VII’s corrupt reign, the institution was forced to relocate to London when the repressive “rey felon” (robber king) regained the throne in 1823. It was only after Ferdinand’s death that Spain’s liberal reformers were able to return from their collective exile without fear of being locked up for their beliefs.

In 1835 the institution was reformed in Madrid during the Carlist Wars when the succession of Ferdinand’s daughter Isabel I was opposed by the traditionalist Carlists who wanted Ferdinand’s brother Carlos to take the throne. Ateneo de Madrid supported the reign of Isabel I, a queen who was later deposed ushering in the First Republic in which many members of Ateneo served; one of its most famous luminaries being the Nobel-prizewinning writer and mathematician José Echegaray, who served as Minister of Education, of Public Words and of Finance during the First Republic before retiring from politics and becoming president of the Society.

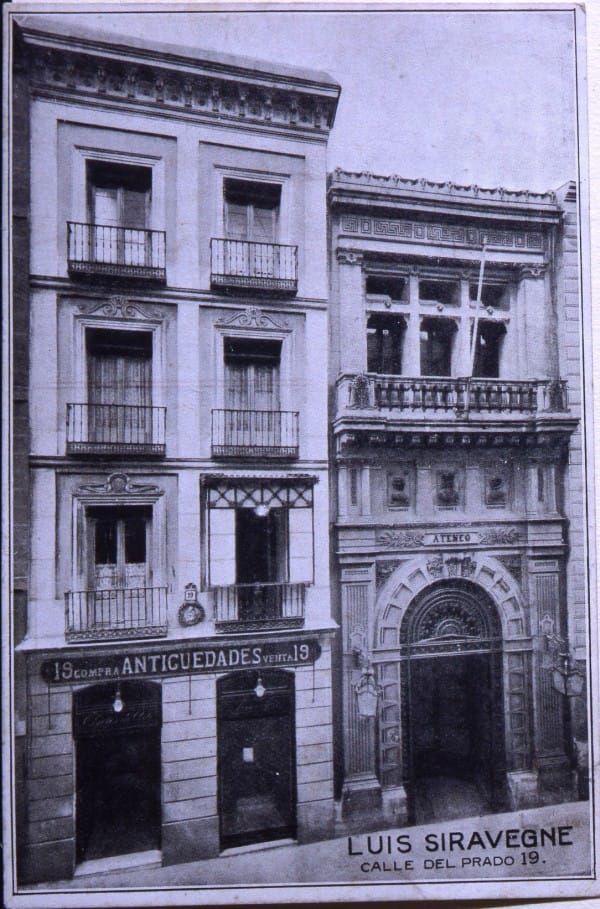

Historic building

After the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, Ateneo de Madrid moved to its current premises in historic Barrio de las Letras in 1884. Its beautiful facade on 21 Calle Prado is well worth taking a look at: above the door are busts of Velázquez, King Alfonso X, and Cervantes: Velázquez representing the visual arts, Alfonso “the wise” representing the sciences, and Cervantes representing literature.

This narrow facade gives the false impression of a small building but anyone venturing beyond the impressive marble staircase soon discovers this is not the case. Beyond the staircase lies a long wood-paneled hall populated by portraits of luminaries from the society’s history. While it’s a bit of a sausage fest, the society has made efforts to redress this, most recently by adding a portrait of writer Almudena Grandes.

Other Ateneo luminaries

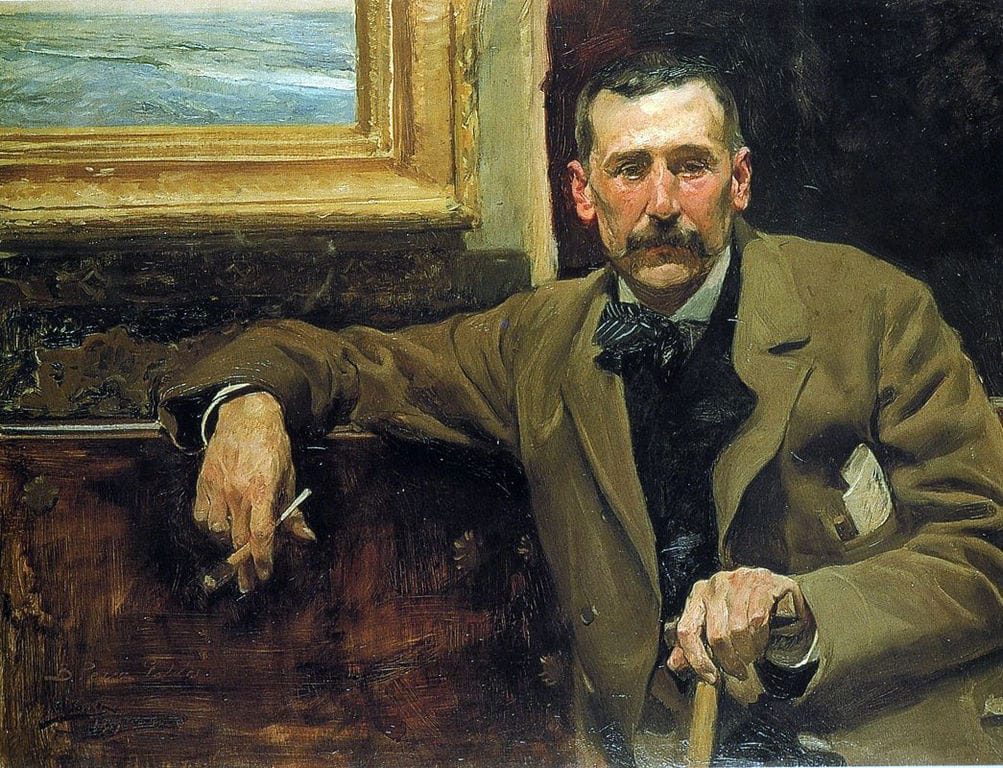

Grandes is by no means the first woman to appear on the society’s walls; that distinction goes to novelist Emilia Pardo Bazán, a trailblazer who, back in the early 20th century became the first female member and even rose to become Ateneo de Madrid’s head of literature. Bazán’s secret lover, novelist Benito Pérez Galdós was also a progressive. Spain’s answer to Dickens, Galdós shone a light on the problems faced by Spain’s working classes and was heavily critical of the status quo. The literary power couple was by no means an exception in political zeal. A hotbed of radical new ideas, the institution has always been linked with politics to such an extent that one of its presidents, Manuel Azaña, went on to become president of Spain during the Second Republic in Spain (1936-1939).

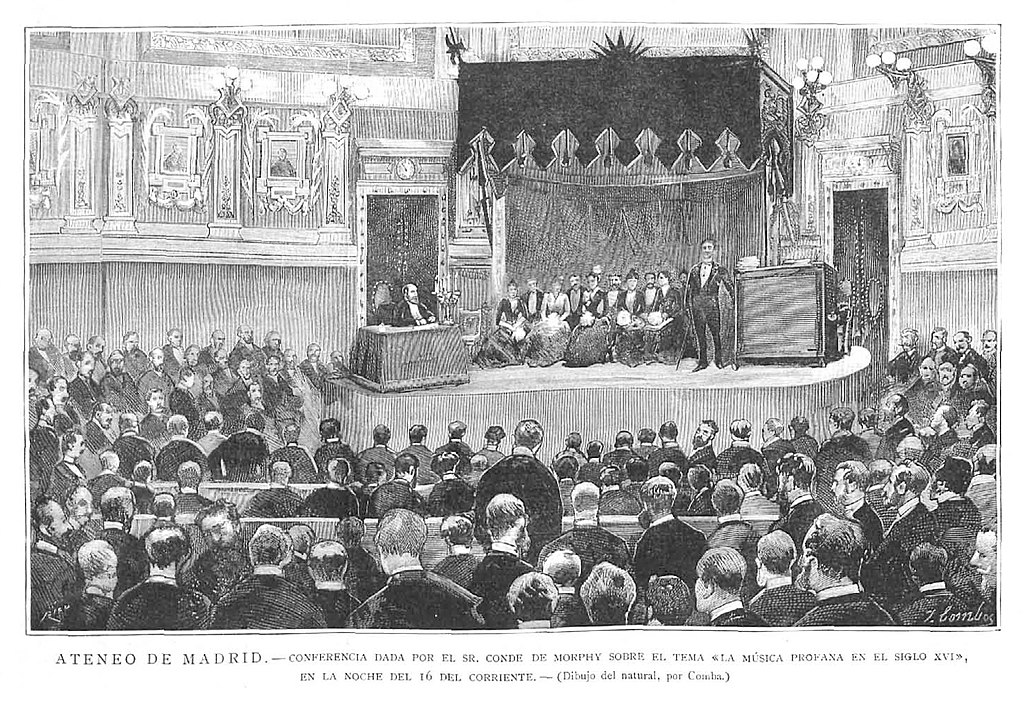

Tertilias

Part of Ateneo’s mission has always been to foster lively debate. Back in the late 19th and early 20th century, this meant hosting tertulias, events in which thinkers gathered to exchange ideas about politics, art, or science. These were held in a room called the Cachería, or China shop, named perhaps for the large ceramic vases that grace its beautifully frescoed walls or, perhaps because the subjects debated there could be so scandalous that the effect was similar to an elephant crashing into a China shop.

Famous figures to grace these heated debates include the famously argumentative playwright Valle-Inclán and the contrarian philosopher Miguel de Unamuno whose inability to hold his tongue in front of Franco ushered in his untimely demise during the Civil War – events immortalized in the excellent 2019 film While at War.

Ateneo today

While Ateneo continues to be a private member’s club, members of the public can visit its beautiful library by appointment, though they do have to pay a fee of €2 to gain access. It’s also worth checking out the organization’s event calendar, which offers a wide range of concerts and talks held in the Salón de Actos, a gorgeous events hall decorated in gold leaf and bold colors.

The future

Though supposedly nonpartisan, Ateneo has always been at the heart of political storms in Spain so it’s no surprise it’s fallen foul of a right-wing local government during a period in which politics has become increasingly divisive. Nonetheless, as its sources of funding go way beyond local government with wealthy private benefactors backing the institution, it seems unlikely that its future is in real jeopardy. It’s also important to mention that Ateneo de Madrid is still free to apply for local government funding for specific projects. As this funding comes from taxpayer’s money, I’d like to see more events throwing open the doors of an institution that though progressive, is to a certain extent only open to a select intellectual elite.

Did you enjoy this post? Would you like to know more about Madrid? Then why not book yourself in for a tour with me, the writer of The Making of Madrid?