Chulapos and majos

If you’ve ever attended a festival in Madrid, you may have seen ladies in polka dot skirts and headscarves hanging on the arms of gents in tight dark trousers and checkered caps, both sporting bright red carnations. These are the chulapos and chulapas who were immortalized in literature and song during the 19th century as bawdy but benign rogues. Emblematic of the spirit of Madrid, they are cheeky, independent figures that are above all friendly to outsiders. But this wasn’t always the case. In the 18th century this tribe was so fiercely nationalistic that it brought them to blows with the establishment on more than one occasion.

Formally, chulapos and chulapas were part of the larger tribe of majos and majas; that is working-class Madrileños living in the more deprived areas of Maravillas (now Malasaña) and Lavapiés (then Avapiés). Proud of their Spanish heritage, they wore colorful embroidered outfits that were quite unlike the French fashions adopted by the upper classes. Rough and ready majos loved macho pursuits like bullfighting, but showed a softer side with their fondness for fandango music. Most were law abiding workers, but some took advantage of the fact that the typically-Spanish long cloak was perfect for concealing weapons, while the wide-brimmed hat ensured anonymity during the execution of a quick mugging on the darkened streets of Madrid.

An enlightened dictator

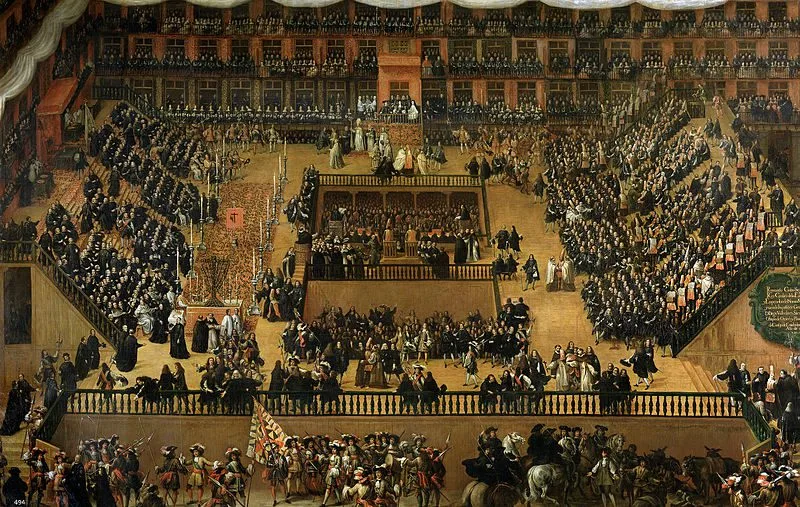

The court of that time – led by Bourbon King Carlos III – was, by contrast, extremely influenced by French ideas. Courtiers largely adopted a French style of dress to match its progressive liberal policies. Reforms were introduced one after another. Street lightning in Madrid, for instance (as a countermeasure to those muggings I mentioned), as well as the liberalisation of the grain trade. It was this last reform that began to sow discontent among the working classes. The price of bread shot up so high that when the king’s adviser Esquilache had the temerity to issue a decree banning the long cape and wide-brimmed hat in favor of the short cape and French three-cornered hat, the people revolted causing the king to flee the city in fear for his life.

Carlos finally made his peace with the majos by withdrawing the controversial dress-code decree, booting out his adviser and appointing majo mayors to each neighbourhood. While the odd street fight still occurred between majos and the people they viewed as Frenchified fops, peace reigned. That was, of course, until Napoleon rolled into town. Dress again became overtly political and it was these flamboyant majos, fiercely loyal to their ousted king (surmising perhaps that it was better the devil you knew), that died by the hundreds in reprisals for the May 2 uprisings of 1808.

Goya was a huge fan of the majos and depicted them over and over again, not only in his tragic paintings of the Esquilache riots and May 2 uprising, but also in more tranquil scenes, playing guitars or taking paseos. He even put some cheeky majas in his fresco of Saint Anthony raising a man from the dead in the cupola of Ermita de San Antonio de la Florida! His portraits of a sexy clothed and nude maja are on now on public display in the Prado, but at the time sparked quite a bit of controversy after being confiscated by the Inquisition. Goya narrowly escaped prosecution for refusing to reveal the identity of the patron who commissioned the paintings. Neither did he reveal the identity of the subject, who some believed was the Duchess of Alba.

Goya’s tribute

Though Goya did have an affair with the duchess, it’s unlikely she would risk her reputation to pose for such a picture. These theories are based on the fact that the adventurous duchess liked to stroll around Madrid incognito dressed up as a maja. This would mean wearing calf-length skirts puffed out with petticoats, white stockings, embroidered bodices and a lace mantilla. Playing dress up must have been fun for this aristocrat, but real life was tough for majos who struggled to get by at the best of times. Losers in the class war, it was perhaps inevitable that they wound up fighting each other.

Which brings me back round to chulapos and chulapas, and by extension to manolos and manolas. I mentioned earlier that the main working class areas of Madrid were Maravillas (now known as Malasaña) and Lavapiés (then known as Avapiés). The majos and majas of Maravillas called themselves chulapos and chulapas, whereas those from Avapiés called themselves manolos and manolas. Chulapo is somewhat equivalent to saucy and refers to the cheeky attitude of the barrio, whereas manolo is derived from the name Manuel which was common among descendants of converted Jews. These two groups were often at loggerheads with each other and come festival season in spring, fights would break out.

Fame at last

During the late 19th and early 20th century, majo culture was immortalized in zarzuelas (plays with musical interludes) and the literature of writers such as Benito Pérez Galdós and Ramón de la Cruz. However, as these works were written by bourgeois artists who had little real contact with the culture they depicted, in this period chulapos and manolos became conflated in the public imagination, hence we are left simply with chulapos and chulapas. Similarly, foreigners would also conflate Madrileño majo culture with the Andalusian flamenco tradition, giving birth to works like Bizet’s Carmen.

If you’d like to see real live chulapos and chulapas strutting their stuff, make sure you attend the Festival of Saint Isidro on 15 May. Not surprisingly the “traditional” Chotis dance you’ll see them performing only dates back to 1850. The dance, along with the threads sported by modern day chulapos and chulapas bears little or no resemblance to Goya’s stunning paintings of Madrid’s original majos. Like everything, chulapos have changed with the times and while their disdain for the French seems to have softened somewhat, they maintain the cheeky majo attitude that so endeared them to the artists and writers of their day.

Keen to find out more about the history of Madrid? See another side of the city with one of my unique walking tours.

Fascinating – for one, this puts paid to the myth that Lavapiés was named after an ancient fountain in the main square; or, at least, it would seem to if the area was renamed. Equally, I didn’t know that Manuel was a typical name of Jewish descendants and that the Manolos/ Manolas were part of the Lavapiés ‘tribe’. This needs more explanation over a beer, I think!

Thanks for the comment. Lavapiés started out as Lavapiés, but at some point became Avapiés, only to later revert back to its original name. Not sure about the fountain, need to do a bit more digging on that one. Yes, we should discuss over a beer though, going to PM you. x

Hello! I always enjoy reading about majos! Thank you. For some further reading on majos and majas, you might try Julio Caro Baroja’s classic essay “Los majos.” In my 2011 book Women, Work and Clothing in Eighteenth-Century Spain, I’ve got a couple of chapters on majos and majas. You may also find of interest an essay I wrote on majos and their working-class or abject roots: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/CHMO/article/viewFile/38675/37397.

Thanks for your reading recommendations Rebecca. Hopefully I will be able to use these to dig deeper into majo culture some time in the future, feel like I’m only just scratching the surface at the moment so it’s great to have some pointers!

Pingback: A Brief History of the Rastro - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Ten Truly Madrileño Terms - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Madrid's Most Problematic Painting - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Quiet corners of the Prado - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Summer in Madrid: August festivals - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: San Isidro Madrid's (male) patron saint - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Hidden Gems: the Hermitage of San Antonio de la Florida - The Making of Madrid