What is the Habsburg jaw?

The Habsburg jaw is a severe facial deformity characterized by a protruding lower jaw (mandibular prognathism) and receding upper jaw (maxillary deficiency) that plagued Europe’s most powerful royal dynasty for generations. This distinctive feature, visible in portraits spanning two centuries, resulted from inbreeding practices designed to keep power within the Habsburg family—with devastating genetic consequences.

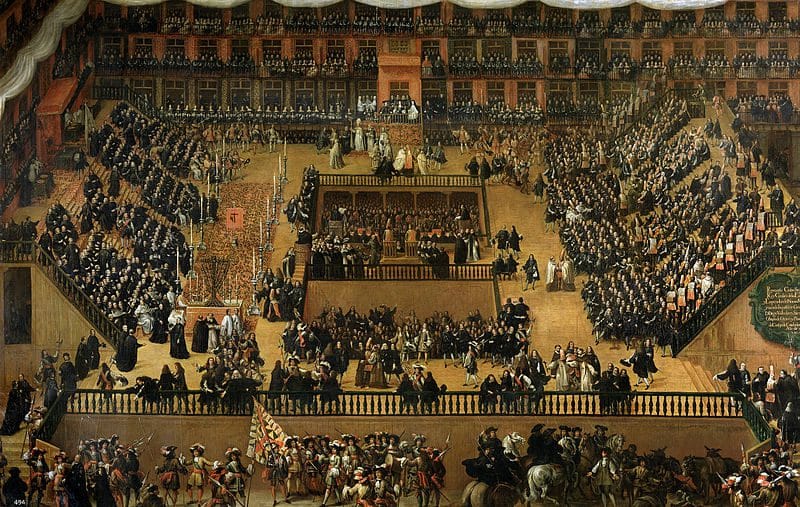

Walk into the Museo del Prado today, and you’ll see it staring back at you from canvas after canvas: that unmistakable jutting lower lip, that prominent chin, that peculiar facial structure that marked the Habsburgs as surely as their crown.

The genetic price of royal power

The Spanish Habsburgs were the most powerful global dynasty in the 16th and 17th centuries but they lost it all to interbreeding. Hoping to keep a tight hold on the reigns of power, six out of eight royal weddings leading up to the birth of the last Habsburg King Carlos II, were incestuous: uncles marryied nieces or first cousins. This wasn’t accidental. The Habsburgs deliberately married within their own family to consolidate territorial claims and keep their vast empire unified.

But genetics doesn’t care about dynastic politics. With each generation, recessive genes for facial deformity accumulated and expressed themselves more severely. The last Habsburg ruler, Carlos II was the product of all this interbreeding. In addition to being sterile, he was afflicted with so many health complaints that he believed he’d been cursed.

Can you still see it today?

Yes — the Habsburg jaw is remarkably well-documented in the royal portrait collection at Madrid’s Museo del Prado, where you can trace the progression of this genetic condition across generations of Spanish Habsburg rulers.

At the Prado, look for:

- Alonso Sánchez Coello’s portrait of Don Carlos (1564): The son of Philip II shows early signs of the distinctive jaw structure. Pictured with a powty scowl on his face worthy of Game of Throne’s awful Joffrey, this viscious little beast (more on that later) wound up being imprisoned by his own father.

- Velázquez’s portraits of Philip IV (Felipe IV): Multiple portraits from different periods of his reign reveal the pronounced Habsburg jaw in one of Spain’s most painted monarchs. Despite his regal bearing, the protruding lower jaw is unmistakable.

- Luca Giordano’s portrait of Charles II (Carlos II): The most devastating example. The last Spanish Habsburg possessed such severe mandibular prognathism that he reportedly couldn’t chew his food properly. Giordano’s unflinchingly realistic portrait shows a young king with an extraordinarily pronounced jaw — a genetic dead end painted in oils.

What were the origins of the Habsburg jaw?

Jutting out in royal portraits since Carlos I, the Habsburg jaw is now the most infamous sign of royal interbreeding. A rather bitchy comment made by Italian diplomat Antonio di Beatis in 1517 described the first Spanish Habsburg monarch as having “a long, cadaverous face and a lopsided mouth (which drops open when he is not on his guard) with a dropping lower lip”.

Carlos, however, was no interbred fool. The child of Philip I (aka Philip the Handsome) of the Netherlands and Joanna of Castile – daughter of the great Isabella and Ferdinand – his parents represented the melding of two great European dynasties. Along with a wide gene pool, Carlos I inherited vast territories and became the most powerful man in the world. While he’s mainly remembered for his astute decision-making, he did set the trend that would doom his ancestors: when it came time to marry, he hooked up with his cousin Isabel of Portugal.

The Black Legend

The son of Carlos I, Felipe II inherited that great big Habsburg jaw and his father’s knack for politics. He’s the astute king who effectively made Madrid the capital of Spain by settling the court here in 1561. He liked to play his cards close to his chest and ruled out of a huge palace in the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains, mainly issuing orders by letter and earning the rather sinister nickname of “the spider of El Escorial.”

Like his father, he married his cousin, María Manuela of Portugal. However, two generations of interbreeding did not produce favourable results. Their son, Carlos, Prince of Asturias, was born with a massive Habsburg jaw, one leg longer than the other and an uneven temper to boot. In time, Don Carlos would horrify the court with his fits of rage, behaviour that convinced Felipe II that Don Carlos was not fit to rule. Barred from succession, Carlos began to conspire with Felipe’s Protestant enemies in the Low Countries and even attempted to stab Felipe’s right-hand man, the Duke of Alba (aka The Iron Duke).

Murder most horrid

Things came to a head after he tried to shoot his uncle, John of Austria. Luckily a smart servant had emptied his gun of bullets beforehand! On 18 January 1568, Felipe II had the dangerous Don Carlos locked away. He died on 24 July the same year. Rumours, of course, went flying that the king had ordered the assassination of his treacherous son. Though it’s thought this was not the case, this contributed to the Black Legend surrounding Spain – horror stories cooked up by Felipe II’s Protestant enemies.

Lessons not learned

Felipe II didn’t learn from this dreadful incident. After his first wife died, he married his first cousin Mary Tudor and briefly became king of England. Mary died before they could have any kids, paving the way for the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I to take over in a turn of events that would lead to the Spanish Armada.

The third wedding could have been a charm for Felipe as he married out of his gene pool to Elizabeth of Valois. The two went at it like rabbits and produced tons of children but not one single surviving male heir until poor Elizabeth died miscarrying a daughter in 1568, just months after Don Carlos died in captivity. Time for marriage number four and you guessed it, Felipe II decided to keep it in the family! Ana de Austria was his niece and produced his only surviving male heir Felipe III, a child Felipe II was none too impressed with commenting: “God has granted me so many territories but has denied me a son capable of ruling them.” These words would prove eerily prescient.

Felipe III

It’s hard to say if Felipe III inherited the monstrous Habsburg jaw. If he did, he covered it up with a pointy little beard. And perhaps this is the only wise decision we can attribute to him. Felipe was fond of many things besides government: card games, hunting, music and dancing. Hoping to dedicate more hours to these activities, he allowed his valido, a smarmy chap called the Duque de Lerma to rule in his stead. Lerma, whose portrait hangs in the Prado, went on to swindle the crown out of a fortune in an elaborate property scam that involved moving the capital to Valladolid and back again.

Kissing cousins and nieces!

When it came time for Felipe III to marry, he got together with his second cousin Margarita de Austria-Estiria. Their union produced a figure whose Habsburg chin and pouting lips were immortalized by Velázquez in numerous paintings. A playboy of epic proportions, fathering numerous illegitimate children, Felipe IV nevertheless struggled to produce an heir within wedlock. His first marriage to Isabel de Borbón produced 10 kids with only two surviving to adulthood. When it came time to marry again in 1649 aged 44, he tied the knot with his 14-year-old niece Mariana de Austria. Their son Carlos would be the last Habsburg.

The last Habsburg

Carlos II’s jaw was so humongous that he struggled to chew his food and his tongue so outsized that he could barely string a sentence together. Hardly surprising if you look at his ancestors. The gene pool had become a muddy puddle and no amount of new blood could turn things around. Perhaps someone had got wise and arranged that the next two royal wives – María Luisa de Orleans and Mariana de Neoburgo – were neither cousins nor nieces, but the damage had been done. Even though efforts were made to nurse him back to health – at one point courtiers placed the mummified corpse of Saint Isidro by his bed – Carlos II died at the age of 38 leaving the way clear for some new blood. From here on in the Bourbons would rule the roost!

However, some say that accounts of Carlos’ ailments were overexagerated by the Bourbons who took power after his death. For more on that you can listen to my interview with the amazing historian Caroline Fish. And while the Bourbons aren’t as famous for interbreeding, they, like any other power hungry dynasty liked to keep it in the family. The awful rotter, Ferdinand VII, for instance, married his own nieces one after another (they were wives number 3 & 4)!