Narratives surrounding Spain’s Jewish converts to Christianity and their descendants (known collectively as conversos) understandably focus on the victimization of this community. Historian Kevin Ingram shifts the perspective a little by asking what role they played as innovators in modern Spain. In the latest episode of the podcast to coincide with the presentation of his book Converso Non-conformism in Early Modern Spain at Secret Kingdoms bookshop on November 21, we discuss their role in bringing change despite persecution to deeply Catholic Spain.

Full transcript below.

Speaker 1: Hello, welcome to the Magian Madrid. Today I’ve got a guest on, his name is Kevin Ingram and he’s a historian who’s been doing a lot of research into the conversors, that is the descendants of Jews who were forced to convert Catholicism.

Now you might think that this is a little bit of a depressing topic but Kevin has a new spin on it and he talks a lot about their interesting role in modern Spain and how they really changed Spanish society. So it’s a really good conversation. Before we move on to the interview I’d also like to add that this is going to be one of the last episodes in this series. I’ve been running the podcast for about a year and I’ll take a break over Christmas.

When I come back after Christmas the podcast won’t be quite as regular so I’m thinking of moving to a monthly format and that’s because I’ll be working on the update to Lonely Planet’s Madrid Guide so I’ll be flat out but I promise I’ll try and keep bringing you content that may be not quite as regularly as before. Anyway, I hope you enjoyed this episode. Hello Kevin, how are you doing?

Speaker 2: I’m fine, thank you for talking to me.

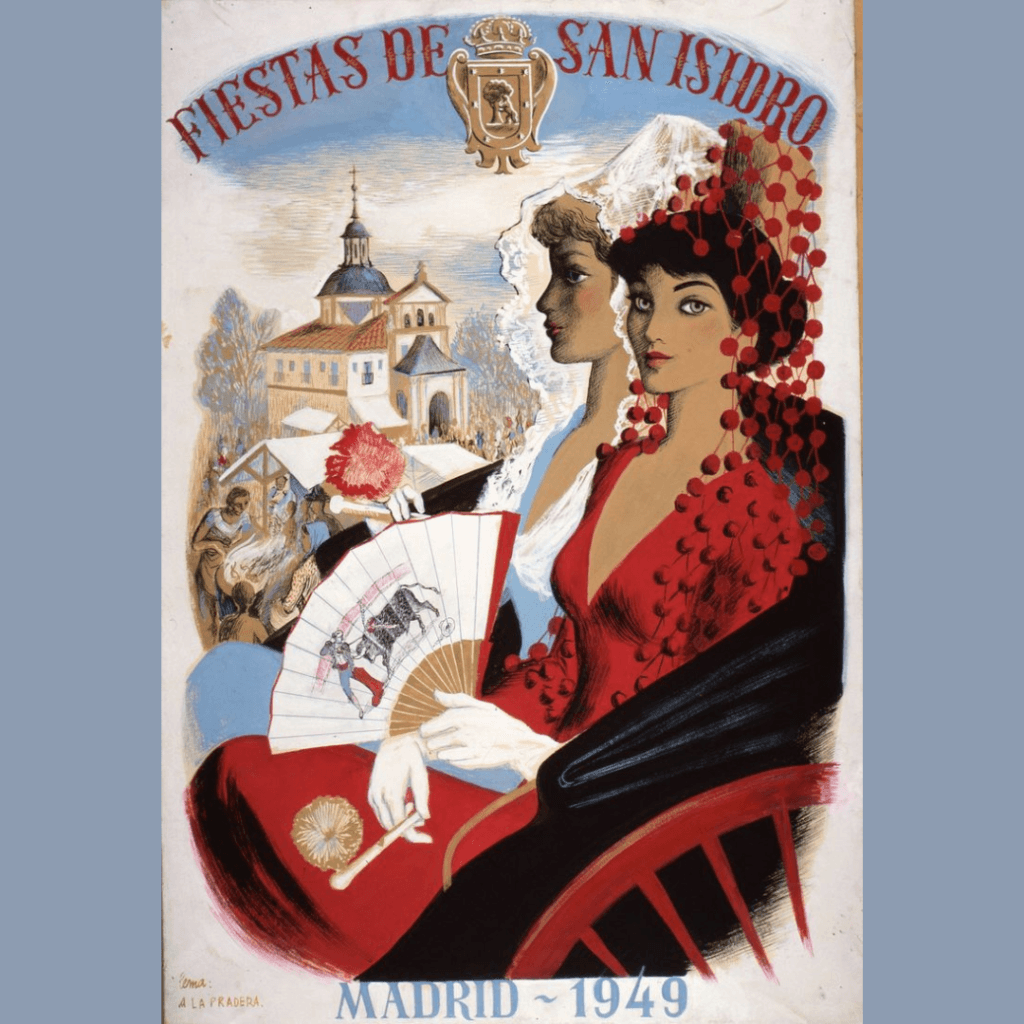

Speaker 1: Thank you very much for coming on the podcast and this episode should be airing just before a special event for you which is on November 21st at the Secret Kingdom’s Bookshop. You’ll be presenting your book which is Converso Non-Conformism in Early Modern Spain. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Speaker 2: Yeah, well this book started many years ago probably, it came out of a dissertation I was writing when I was doing my PhD in University of California San Diego. I won’t go into it now but I became interested in the Conversos. I was researching a group of humanists in Seville and it occurred to me that almost all of them were from Converso backgrounds, some very obviously so, some not so obviously so because for various reasons they wanted to disguise their Jewish ancestry.

Speaker 1: Yes, so we should get started with defining the word Converso but before we jump into that let’s just tell everyone that they can join this event and see you talking in person about this book and ask you questions if they want and get their hands on a copy because I believe it’s on sale in the bookshop.

Speaker 2: Yeah, they’ve even placed it in the front of the bookshop in the Scattarati.

Speaker 1: That’s the front window for anyone who doesn’t speak Chinese. And the event will start at 8pm and I believe it’s on Eventbrite, is that right?

Speaker 2: That’s right, yeah or in the bookshop itself. Or just come along on the night.

Speaker 1: Yes, you can chance your arm with it. And the secret kingdoms is on Kaya Monatine if people don’t know that but I’ll put a link in the show notes. And you just gave us a brief overview of how you came to write that book but before we get into it all we should kind of define what is the Converso. So can you tell me about that and how the phenomena began?

Speaker 2: Yeah, okay so most people think that the Converso’s that the phenomena began in 1492 when the Jews in Spain were given the ultimate either to convert to Catholicism or leave the country. And as a result of this many of those Jews remained and they converted to Catholicism mostly because it was so difficult to think in terms of the life outside of Spain when they had to leave all their possessions behind.

Speaker 1: Yes, yeah.

Speaker 2: So it was the birth of the Converso’s?

Speaker 1: I know, I just heard they were so engulfed into their clothes and things because they had to give everything up and sort of you know so I was wondering do you know what proportion of Jews decided to leave and how many decided to stay?

Speaker 2: Well this changes all the time originally particular figures were given that the Jewish population was probably 150,000 and maybe 100,000 left and 50,000 states. Now I think a more reasonable figure is that the Jewish population was at Spain was about 80,000 and over half remained perhaps 35,000, 40,000 left most going to Portugal.

Speaker 1: Okay and you’re saying most people believe that that was the start of it but you’re saying it started earlier this phenomenon?

Speaker 2: Yeah well there was something called the 1391 Pobrom and this was in the year 1391 there were uprisings against Jewish communities throughout Spain it started in Seville and after that year subsequently in the wake of that there was a mass conversion of Jews to Christianity again under duress, a threat for their lives basically and so they not immediately a lot converted immediately but in the next two decades two or three decades we find that a large number possibly as much as half the population of the Jews at the time converted to Christianity and this really was the start of the converse hope phenomenon.

Speaker 1: Yeah I kind of go against my own advice here and going off down the side road but I do know that relative to the rest of Europe Spain was kind of more say Nenian if that’s the right word probably not tolerant is the best word of Jewish communities because in UK certainly I mean in England certainly they were treated far more harshly but this anti-Jewish sentiment was there for quite a long time.

Speaker 2: Yeah that’s right it was as you said more tolerant. Spain was a multicultural environment there were lots of people Muslims in the country large population of Jews and the Christian society needed these the Jews were quite intellectual they were also good for the economy they were businessmen and so they were needed and what we find is that even after the Jews had been expelled from England and France in the 12th century the Jewish population thrived in Spain but as a result of proselytizing from the new mendicant orders the Dominicans and the Franciscans especially the Jews were put under a lot of pressure during the 14th century this is leading up to the 1391 program to convert to Christianity so we find although they that in the 12th and 13th century their position was relatively stable progressively it got worse up until 1391 as I said when there was this program when you would find that through this these proselytizing campaigns through this pressure put on the Jewish communities through pressure from the rank and file old Christians in the cities that they were they were forced to convert

Speaker 3: and

Speaker 2: so we get the first safe wave of conversion.

Speaker 1: I also think that when we use the word conversos I was wondering if we should use today or conversos or what did people generally call Muslims who had been they were later forced to convert.

Speaker 2: They called moriscos the Muslims we usually use the term moriscos. Yeah and then for Jewish converts we can call them new Christians we can call them conversos or fureo conversos the old term was

Speaker 4: morano maranos but marano or some

Speaker 2: people still use it to mean a converso that maintained his old religion in other words he was sort of a backsliding Catholic he continued to practice he was a Judaize but the term generally today is not used because marano means pig so as well so in Portuguese so we don’t we tend not to use that term any longer so converso is the term I use okay okay

Speaker 1: it’s like the word which is mudeha which the term mudeha which is also kind of insulting to I mean I’m talking about former Muslim populations who this is kind of like a tamed animal or something in Arabic but sort of lost its association so much that a lot of Spanish people use it not knowing that it’s a priority.

Speaker 2: Yeah the term mudeha was used for the Muslims who remained in in Christian territory after the recon the recon quest so those who were outside of the kingdom of Granada which was a Muslim kingdom up until 1492 so those that decided they were going to remain in Christian territory they weren’t persecuted they were they were even allowed to maintain their mosques although they couldn’t build new ones but they could repair them and so there was a small population of Muslims from the mid 13th century onwards and those were designated mudehares.

Speaker 1: Okay all right and of course both these groups were then persecuted by the Inquisition so can you tell me a little bit about that?

Speaker 2: Yeah well if I just go back a step so first thing is this should not be complicated but it can get quite complicated the term converso was applied by an old Christian community to not only the converse because it means convert but to their descendants as well so it doesn’t matter how far you were away from the original conversion if you came from a family of the Jewish background you were known as a converster.

Yeah so what happened then was that you have a large number of Jews that have now converted to Christianity in the 15th century as a result of that of course they now can enter into Christian society into Christian positions in town halls and universities in the church so whereas before they were very restricted as Jews in what they did now the society is open to them and as a result they are under

Speaker 1: I’m sorry they are under a certain amount suspicion then

Speaker 2: they’re definitely under suspicion and they’re under but more than that there’s there develops quite a lot of envy towards them especially sort of a middle sort or a middle class converso that is prominent in the large cities like Toledo for example or Seville who do tend to do very well in that society they do well in business they do well in the universities and they do well in politics as well they work for the the noble families as accountants and as teachers as well and so it’s not just that there’s suspicion towards and there is some suspicion towards them that is definitely true because all Christian society still believes because they stay in the same neighborhoods they still have access to Jewish communities as well that may be in private they’re Judaizing which I think in the first generation and possibly the second generation is quite true although that that becomes less and less as we go through the generations but the major problem I think or at least an equal problem is the fact that they are doing well when all Christian society wanted the Jews to convert they were very happy with that but what they didn’t want them to do was compete with them in society and when they compete and they seem to be doing it at an advantage then this starts to create problems so you have one the suspicions but two the kind of envy of people who you’ve associated or you’ve thought of as people who are inferior to you now they’re holding positions that are much better than you in society and this creates an enormous amount of enmity towards the convertible in fact by the mid 15th century there’s more enmity towards the convertible than there is towards the Jews who have quite a subjewed community by this stage and this and two things happen as a result of this one we get something called the Olympiated Disangrae Statutes now Olympiated Disangrae was a statute that was created to make sure that conversos didn’t enter into public office or church office public office enter into universities very often enter into the town guilds so they were restricting their access to a society basically placing them in the same position as they’ve been placed of their ancestors have been placed as Jews which is obviously to them to converse a completely unfair what have we gained by converting to Christianity that was the one thing that happened and that was a major problem for conversos the second thing that happened was that there was so much there was so many attacks on these Jewish communities that the sorry these converso communities that the Catholic monarchs is a bell and ferdinand in 1478 were persuaded to create an inquisition known as the Spanish Inquisition there had been other inquisitions before Roman Inquisitions there was a famous medieval inquisition but this was a Spanish Inquisition which had nothing to do with the papacy it was created as a council of court it was created by the Catholic monarchs and it was there to make sure that conversos were good Catholics in other words it investigated claims that converso families were backsliding that they were observing Jewish rights in private this created a enormous amount of tension and a normal enormous amount of pressure on the conversos themselves

Speaker 1: could they be denounced by somebody

Speaker 2: they were they generally they were denounced by it started in 1479 there in the end I think there was something like 12 tribunals throughout Spain and Aragon throughout Castile and Aragon it started in Seville in 1478 and then spread to Theodard Real and Cordoba and Toledo etc and what happened was that there was a period of grace and then in that time the conversoes it’s horrible this is a horrible thing the conversos were asked to come to the inquisition and declare if they had been they or their family members had been observing Jewish rituals or rights in private to come and to tell the inquisition and if they did that they would probably only get a stiff sign you know they wouldn’t be burned to the stake for example so which of course many did but then others their neighbors very often all christian neighbors would come to the inquisition and say there’s something you haven’t come forward and we know that they’ve been observing Jewish rituals in private so this is what happened with the inquisition and as a result of which of course many many Jews were in those first years of the inquisition at the first two decades especially were burnt at the stake okay so that’s what’s happening with the conversoes now the other thing is that it was felt that the conversos would never be good christians while Jews were present in the country so while as a Jewish community there are Jewish rabbis the conversos then have access to their old religion and it’s going to be much more difficult for them to be sincere christians and this was behind the the edict of 1492 by the catholic monarchs giving the the the the remains of that Jewish community the auction either convert also to christianity or leave the country and that so we’re back at 1492 but a lot had happened before this before in the 1492

Speaker 1: yeah and then going on from then by understanding is that the inquisition was very powerful but gradually its influence began to wane as the through the generation so you carried on having the autist affair which with the trials of faith but not very many people would end up being burnt at the stake it was more kind of finds being dished out and people sent into exile and things like that and then you know this this tension kind of died down a bit is that is that correct walrus yeah um

Speaker 2: i we don’t have a 2000 or so Jews would move up converse was probably burnt at the stake in the first 30 years many many were imprisoned lost everything i mean the other finds were harsh and also you know the other ways of castigating them you know sent to the galleys those kind of things but probably yes the the largest number of Jews were sorry converse of were burnt at the stake before 1520 after 1520 the inquisition sort of moved away from its interest in judaizers to its interest in uh in protestants so after luther comes along the the worry then was that um that there were protestant cells being created in spain itself and people became very anxious about the inquisition itself became anxious about that so they tended to inquisitor to investigate uh people who they thought um humanists um and others members of the clergy who they thought were reading protestant literature um so but the thing was that and you’ll see you’ll read this in the in the in the uh general history books that there was a move away there was an interesting move away from jews an interest in protestants um but they were the same people they were the same people they they came from the same families very often it was the converse those that became interested in protestant which makes sense they’re just interesting no no no no people just think oh yes well no so this so the converse those were off the hook no they were the same families very off they were same intellectuals uh it made sense to converse so you’re not at home in a Catholicism and the Catholicism are the rituals of Catholicism and you’re looking to create a Catholicism that is just based on some just basic principles what eras must they were Erasmians before protestants as well what Erasmus said was the uh was the philosophy philosophy of christ the philosophy of christ which is just based on the sermon of the mounds um and that obviously appealed to people who you know it allowed them to engage more with with with christianity it was like a pared down christianity that they could you know that they felt much more at home with so there’s so again um this is where i this is where i come into the story this is my interest in the converse those it’s the converse those as reformers in 16th century spain up until

Speaker 1: really yeah are you saying you stumbled upon a few figures during your research

Speaker 2: a lot um they’re all they’re nearly all all all the great reformers all the great spanish humanists um they’re you know almost to a man a woman are from converse of

Speaker 1: background how would you identify them as conversers so were these people always having to reveal their ancestry

Speaker 2: um no this is this is something that you it’s really a lot of it really is through circumstances we have a lot of information for example you know the great um mystics uh and the early uh jesuits themselves which also is a largely conversants you know the first jesuits are largely come from uh converse of background we have a lot of information on on some of those families and that’s very clear that they are conversant um teresino vavila for example great mystic we know that her family um were uh prosecuted for judy i think in tolle though so we know that they are other ones really um you have to do a little bit of research into their into their family background into their into their intellectual environments into what they’re writing as well to see that what they’re doing is really is promoting conversos instead of attacking them promoting people from a jewish background instead of attacking

Speaker 3: but that’s what i got involved with

Speaker 1: is there any truth to the idea that there might be certain family names as that could identify you as a conversor was that not true at all yeah um

Speaker 2: there are there are certain family names for me well actually i’ve got here because i was thinking about this before before this talk and i remember that um some years ago there was something called a composithion that was found it was a composithion this was a list of names in 1510 in civill and these were names of um conversos uh who they joined the list because they were paying a certain fine or a sum of money so that their ancestors names who’d been the ancestors who had been convicted of judy i think many of whom were burnt at the state so that would be wiped from the inquisition records who so what they gave in the composithion was their names and professions and from this we get a very good idea at least in from civill about the family names so all the names they had taken um when they converted from judyism to christianity and there are many many names of cities and that seems to be where they actually converted so the nature’s city so if

Speaker 3: i i’ve got a list here so this could you give an example yes yeah um okay we have lots

Speaker 2: of um professions not so much um but there are certain surnames which seem to be with which time and time again um conversos adopt nunius rodriguez peris lopez sanchez and andi lots of them those are the names i’ve now as far as their professions are concerned which i think is also interesting again um very often there’s a a continuation from the professions that the jewish forefathers had um but they they’re they’re fairly limited the the conversos are are urban dwellers generally i mean there are farmers there are people in the rural background but generally they’re associated with kind of with an urban environment so what we get in this composithion is lots of jeweler’s merchants spice merchants um obviously rag merchants uh moneylenders tailors hosiers button makers silversmiths chemists notaries and clothes merchants those generally are the other kind of professions that they they took on

Speaker 1: I’ve also heard in Madrid, Tanners in La Vapier.

Speaker 2: Tanners, yeah. Yeah, Tanners is true. And the leather industry, and also could see shoemakers. They were all cobblers.

Speaker 1: Your interest is in, you know, you saying that there’s really amazing figures that you’ve discovered who change Spanish society or the modernizers. And bring the whole book so we don’t have time to go into all of them. But would you like to maybe highlight one or two of these people?

Speaker 2: Yeah, well, it starts really with the the. The converse those converse to intellectuals were attracted to humanism. Humanism is it was important to them because the idea of the humanness, which goes back to obviously associating the early Italian humanists associated with the classical community of Rome and Greece. And it was a community that you gained that your nobility came from merit from what you’d achieved in society, not through blood.

And this was very interesting, obviously, to converse also, because they’ve been marginalized through their blood. So the idea was if you can be a noble by merit, that’s important. As well as Christian humanism, which comes from Erasmus, the idea is that prepared down Christianity, which is available to everyone. So they’re very, very much attracted to humanism. And they’re also attracted to mysticism because that is a private Christianity, which you don’t have to worry about anybody except your own.

Your own access to God. So we get all the early great mystics, Teresa of Avila, Juan de Avila, Luiste Leon, Luiste Granada. These are names that are not so well known today. Well, obviously, if you’re an academic, you’ll know, but they were tremendously important at the time.

Speaker 1: St. Teresa is still very well known.

Speaker 2: And I think Teresa is still very well known.

Speaker 1: And what was that? Did she come head to head with the Inquisition at all?

Speaker 2: Yeah, to start with, because, you know, we’re talking about an environment which is post-Tridentine, was after the Tridentine Council, after the Council of Trent. So we’re talking about a Council of Reformation environment where the church was very sensitive to anything. They wanted to control everything. They were worried about Protestantism. So there was, after 1565, which was the end of the Council of Trent, there was a greater emphasis on controlling that, Christian society, Catholic society. And mystics, as you can understand, were outside the control of that society.

You know, mystical visions are outside the control of that. So Teresa and her supporters were investigated many times by the Inquisition. Of course, now we think of her as the great saint of Spain. But at the time, she was a character that was suspect. Any other figures you’d like to?

Oh, yeah. Well, again, you know, people are not so well known today, but all the great Spanish humanists from Antonio Navarra, Juan Luis Vives, who was both his parent, well, his father was burnt at the stake. His mother was exhumed.

Her bones were exhumed and burned at the stake for judyizing. Vives was a great friend of Erasmus, the Valdez brothers, Juan and Alfonso Valdez. Alfonso Valdez was the great secretary of Carlos V. These were all early, these were all early humanists. Veneto Arias Montano, Juan de Mariana. These are just people off the top of my head. But they were the creme de la creme of the intellectual life in Spain.

Speaker 1: So you said these people might be taken to court by the Inquisition. What would the process of that look like?

Speaker 2: Well, to start with, when the Inquisition tribunals were set up, as I said, the first one was in Seville. And then and then every couple of years, it seemed like another tribunal was set up somewhere else. So as soon as the tribunal was set up in a city, then there’d be something called an edict of grace, which was a grace period.

It was a period of three months when conversors could come along. And if they had anything to declare to the Inquisition, they could clear their conscience. They could come and they could tell the Inquisition. And then they would get off with a fight.

Of course, it would be noted who that converter was that had been judiizing. What family was from and whatever. And and and this was used against the families very often later on. So, you know, this you didn’t get scot free. Nothing was scot free with the Inquisition.

Speaker 1: Was he told what they were accused of?

Speaker 2: Well, at this stage, if if you just came and you and you told the Inquisition, you’d probably say something. I imagine that most conversor found what they wanted to do. They didn’t want to get investigated by the Inquisition. They thought, OK, we’ll pay a fine and we’ll we’ll give ourselves up to the Inquisition. And we’ll tell them something.

They copied it, tell them everything. But they said, oh, yeah, you know, occasionally I yeah, I observed the Sabbath and. Which was which was known to the Inquisition anyway. They knew that that jurors and conversors who were observing their old faith would on a Friday, they would cleanse themselves, they would bathe and they wouldn’t cook and and things of this nature. They certainly, you know, during that day, they would work.

And so they say something like that. I don’t work on a Saturday. I have to work on a Saturday or, you know, I mean, they I generally all the family bates before the Saturday before observing Saturday, something like the Sabbath.

Mm hmm. So they would be OK. Now, so the other ones who didn’t come. And give themselves up to the Inquisition or even later still, you know, that they were suspected of being judyizing in the community, then somebody would come to the very often come to the Inquisition and they would say, I suspect so and so. You know, Juan de Sevilla or Juan or Juan Núñez or Sanchez or Herod of of judyizing and then the Inquisition would call them in and they would they would ask them, say, you know, what’s this all about? And they give them a chance to say, well, I have no idea what this is all about. I don’t know.

Speaker 1: You’re able to make accusations in onerously or with a always.

Speaker 2: You never knew who you’re the person was who was making the accusation. Accusation. Hmm.

Speaker 1: So that said, open door to people to exploit that. Completely.

Speaker 2: It was completely. And of course, the Inquisition, then it’s not like a trial now. It’s the Inquisition, then those whether they were satisfied, it depended on the on the individual inquisitive, whether they were satisfied with the explanation. Oh, no, you know, I’ve always had problems with this neighbor.

It’s nothing, whatever. And then they would bring the accused could bring in witnesses for the accused. And they would say, oh, yeah, it wasn’t a good Christian.

I haven’t seen anything. And if the Inquisition are happy with that, they’ll probably let it go. If they’re not, they’ll just say they’ll leave them in. They’ll leave them in prison for a month or so. And they’ll say, OK, they’ll bring them back out again.

And there are some same questions. So they would they like to relieve themselves of their sins or whatever. So no, there’s no sins or whatever. And if they still, if they still don’t believe them, then they’ll put they’ll torture them. And then under torture very often, of course, the people would say, yeah, you know, I’m duty. Well, were they dutyizing or were they just they just wanted to escape the torture? And very often conversive would say later on. No, I only said that to the torture. But this was the process.

Speaker 1: There are some misconceptions about the kind of torture that they would assist people to because that was very clearly stated by the Pope that they weren’t allowed to draw blood. I know that they had to use methods that, you know, the idea of the Iron Maiden and everything is a little bit. Not really correct.

Speaker 2: No, they would torture them. They would stretch their limbs and so they, you know, so their limbs would have a place and they would tie their stomach so that their their intestines would would sort of come out of their stomach. Those kind of things. There’s no blood necessarily.

There are and then waterboarding, of course, in a famous waterboarding. We now have so much that was used quite a lot. So, yeah, it was sort of, you know, stretching them. And I mean, basically, I mean, obviously, I mean, it was. Very aggressive torture.

Speaker 1: And generally people fessed up the very worst that could happen to you. Still, you get burnt at the stake, but this happened to very few people, right?

Speaker 2: Yeah, you know, it did continue to happen. But he and not not the same, not to the same degree as those first, as I said, the first 20 years, very often what would happen then was that so they would, the inquisition would decide on the fines or whatever of these these convicted conversors, if they convicted somebody, then if it was a first offense, you wouldn’t be burnt at the stake anyway. Then you would be reconciled to the church.

We’ll call it a reconciliation. And you would you may be you may be whipped. You may have a substantial amount of your property taken from you. But you wouldn’t be burnt at the stake. The people who were burnt at the stake, they were known as a real ah, how those strange word because you think relaxed. It certainly wasn’t a relaxing thing.

But if they were called real, I thought. And then they were given to the secular arm of the inquisition because the the the the inquisition, the clerics themselves didn’t want anything to do with this, you know, this this wasn’t the holy thing to do to burn somebody at the stake. So they were to give into the secular arm taken to the outskirts of the the city very often in Madrid, for example, the. The. The place of the Alcalá was often used to burn. Some people say that much later.

Speaker 1: I don’t want to burn the city down.

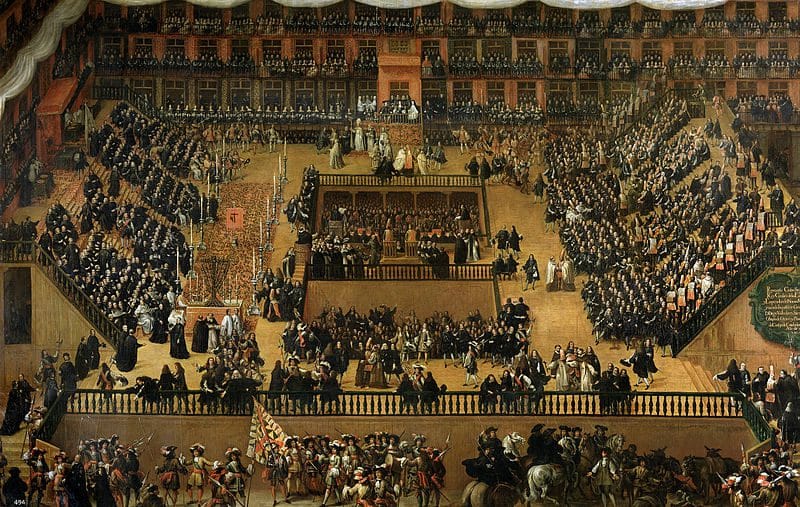

Speaker 2: Yeah. So what so what you had was you had a collection then of people who were ready and then on a day you would have something called the out of the say. And they’d be paraded in front of the town dignitaries very often. If it was Madrid, the king, the court, but that took place in the at least in the 17th century in the platter, my or and then the sentences were read out to them and those that were reconciled to the church would go off and. They would probably get to be fined or to be placed in incarcerated in their homes very often for for a certain amount of time. And the others then would be burnt at the stake. That was that was the process.

Speaker 1: And so Teresa of Avanille was investigated by the inquisition. And this is this period. I believe it’s the 16th century, right? Yeah. It’s split the seconds time. So which he. That’s quite scary for her to stick her neck out and push for reform in the church. But she did so. What was the kind of upshot of her being investigated?

Speaker 2: It was for something they called Alhambra being an Alhambrago. The Alhambrago again, they were mostly conversos, but they the sect but wasn’t really a sect. It was a movement that began in and around Guadalajara in the early 16th century. And they were mystics, but they were private mystics. They didn’t follow the precepts of mysticism, which was OK, mysticism, which was the Franciscan mysticism. And they believed that or at least it was said of them. They believed that they could receive God anywhere through mystical.

They didn’t have to do anything in particular. They just had to open themselves up to God’s love and they would receive the God of the love of God. And at that moment, they were pure. See, they didn’t have they didn’t they didn’t need the sect.

That moment they were pure and in their purity, they couldn’t commit sin. And so it would set of them very often. Oh, yeah, well, this is this was a good reason for licentiousness and that they were they were screwing around. Or but of course, really, the whole point of it was that they they could gain God’s love and grace outside the confines of the church. That many of them were happy with anyone.

So that’s that’s that movement. And then it then throughout the 16th century, mystics or people who were associated with mysticism from time to time got accused of being an Alhambraudo as well. And she was that was the case of of Teresa and early movement. They felt that she was good, that the mysticism somehow wasn’t good mysticism. It was sort of the devil somehow was involved.

Speaker 1: And any other ways that conversos change Spanish culture? What are the other ways that they change their culture?

Speaker 2: Well, I mean, that was the way that they attempted to change Spanish culture through through the humanist movement.

Speaker 1: Religious reform and religious reform.

Speaker 2: Yeah. And looking for sort of greater toleration, you see this in the conversos works very often, is that they’re looking for a more tolerant society. That’s true. Yeah, that was the way they change society.

Well, if you want to look at the. Conversos in commerce, you’ll find that, yes, that they would at the forefront of commerce in Spanish commerce in the in the 16th century. And I’m very often not only the trade, but the house of trade in Seville, those the map makers. Really, the the Council of the Indies and the House of Trade in Seville. And that was the two groups that dealt with the new world and all the trade coming from the new world and all the communities in the new world. The conversos were very active in that as intellectuals and as and as the merchants.

Speaker 1: And how what has been the response in the Spanish academic world about the this research that you’ve been doing into this community?

Speaker 2: Well, you know, today there’s a new. A new generation of historians and they are much more. Accommodating the earlier. Spanish academics. Were resisted the idea very often. That conversos were so prominent in what they understood as Spain’s golden age. And the golden age was that period of the 16th century of letters and of the growth of the the empire, which was generally thought was the result of kicking out the Jews and kicking out the Muslims from Spain. And then this great old Christian community now. Having purified itself, created its great golden age.

But of course, that is an absolute lie. The people that were the forefront of this golden age were those people from the families that you kicked out. They were from they were new Christians very often. And so there was a lot of resistance to that. But more and more people are getting on board with it. But what I find is that instead of tremendous resistance, there’s just half resistance now.

I think, yeah, OK, the converse those were there, but they weren’t that prominent. And we still have a basically old Christian golden age. Which isn’t the wrong way of looking at it. The golden age came out of the friction that was created in the 16th century through those expulsions and through this new group of people that was coming into society and they wanted to change things. And if you don’t recognise that fiction, you will not understand Spain’s scope.

Speaker 1: And that’s a golden age of cultural flourishing. Can you name a particular figure from there?

Speaker 2: The great savante comes from a converse of background. From my from my I’ve looked into the background of. Diego Velázquez, the painter Diego Velázquez is. The paternal side of this family came from Portugal. And there’s there’s good reason to believe that they were also. He was also from Berserpac. In fact, to enter into the noble order of Santiago. He adopted another family, his grandparents. He his grandparents were of Juan Velázquez Moreno and Juan and Mejia. He sidelined those for another family in Seville, another Velázquez family that weren’t his family at all.

But they did have a more acceptable profile of being the Dalgos or sort of lower nobility. And he exchanged it exchanged those for this. He exchanged this real maternal grandparents for those. So he could enter into the noble order of Santiago, whether he did that because the maternal grandparents, who actually were. Tailors. Were were from a Jewish background as well, or whether it was just the fact that they were tailors and so this would have been accepted. So I don’t.

Speaker 1: And. That’s your next big project, though, isn’t it? It’s Velázquez, right?

Speaker 2: That’s right. Yeah, I want to look at the last gift as. Not as the last gift, the person who is very often seen as the person that was created at the court of Madrid of Philip Porto. Somebody who came out of a humanist background in Seville, which was heavily conversa. Those humanist community in Seville was very much conversa. And I look at the last gift as a person with a humanist agenda. And this this humanist agenda is also influenced by his own background, which I believe to have been a conversa, a conversa.

Speaker 1: Hi, interesting. So maybe we’ll have another conversation about that in the future. Love to. But for now, is there anything that we haven’t covered that you felt like you you’re really burning to say?

Speaker 2: After 25 years on this, I’m not burning it any longer. I’m about smoldering sometimes. Smoldering very often when I read. I read in when I look at Wikipedia and I’m looking at somebody who I know comes from a conversa background and they say so and so, who was from a well known Hidalgo family from the Asturias. It’s nonsense. All of these genealogies that we very often scholars refer to that were created in the 16th and 17th century, they are not worth the paper they were written on. They’re all made them. It’s nonsense. And and and hence, you know, because the idea I do.

Speaker 1: Oh, sorry.

Speaker 2: No, you get these intellectuals who come from the Asturias, you know, or from or from the north and the mountains of the north, because that was felt that those were pure because they discape the Muslim influence they fled to the mountain. But in their day in the 16th century, they were regarded as country bumpkins, these people. There was no reason why they weren’t the Internet. They want the intellectual community of Spain. But if you if you look at your Wikipedia articles on some of these great Golden Age figures, they all seem to come from come from, you know, from the Basque country of Asturias, which is reasonable. But it’s repeated time and time again.

Speaker 1: I guess the Hidalgo thing is something people might cling to because they were given sort of minor titles. It’s like minor nobilities, you say, in exchange for having fought on the Christian side back in the day. So maybe it’s kind of a proof of having been, you know, very crusading on the part of of the Christian side in medieval times.

Speaker 2: Yeah, possibly, except that there weren’t. You didn’t you weren’t given a you weren’t given a title, or you weren’t even given a piece of paper, a sort of, you know, as a kind of license saying, oh, yes, you’re from the Hidalgo family. It was just accepted in a community that you were mostly because perhaps you had a little bit of land and you were a little bit better. And so you were seen as an Hidalgo later on. Later on when the king went when Philip II, Charles V, Philip II, Philip III, when they were strapped for for cash, they sold. Certificates of Hidalgo, but the people that were buying those certificates of Hidalgo were conversals.

So, yeah, I mean, you know, they, the, yeah, exactly, you know, they wanted to clean up their background. And so once you’ve got your certificate, no, people’s asking. And I tell you one anecdote before before I leave you, yeah, throw me off.

Speaker 1: I’ve got my two last questions to ask you before we finish anyway, but tell me your anecdote first.

Speaker 2: OK, well, what happened with today? We were talking about today’s the day of the law. The father, Alfonso Sanchez, once the family was accused of Judaizing and then by the Inquisition, they left Toledo and they went to live in Avila. So, you know, they set up a home in Avila. He was a silk merchant of Therese’s father and they did very well for themselves and he clearly wanted to join the ranks of the Hidalgos. And so what happened at the time was that you could you could gain that you buy very often if there was a local tax and you refuse to pay it, then you would be investigated, say, well, you know, no, I’m an Hidalgo.

I don’t because nobility didn’t pay taxes. OK, it was only the ankle fund. So that is exactly what he did. He he said, no, I’m an Hidalgo and I don’t need to pay that tax. So the investigation, well, the investigation basically was that he bribed an enormous number of people to say that he gained from Hidalgo background, spent an enormous amount of money and he got his certificate. Or he was about to get it when somebody decided that they were going to they were going to check the Inquisition records and they found out that the family actually had been prosecuted for Judaizing one generation back. Because he’d spent so much money on this, they didn’t take his certificate of Hidalgo away from him, but they said he could only be an Hidalgo in Avila. So later on, Teresa’s brother, who had left, he was he was a merchant. He had left Spain and he’d gone to live in Peru. And he said, can you send me a copy of the family’s certificate of Hidalgo?

And she said, yeah, this may take some time, but I think you’ll like the result. But when we do know, because we have a copy of that certificate and the sheet that the person who copied it took out only Hidalgo in Avila.

Speaker 1: So then no one’s going to be able to check over there anyway. You’ll get away with it. Well, it’s been delightful talking to you before I wrap up. I want to ask people two questions. The first one is what’s your favorite place in the city?

Speaker 2: Well, my favorite place is the Richiro or living very next to it. My favorite watering hole or going out for a meal. I just I just just love the terrata of the of a plataria, which is a bar restaurant, which is over the road from the Prado. So that’s my favorite place.

Speaker 3: I’ve been for a while to go to to eat out. OK, good prices.

Speaker 1: Nice one for that tip. I’ll be writing the new the only planet guide soon. So I’m always on the lookout for new tips.

Speaker 2: Oh, OK. I’m about coffee central. I would have said coffee central, but now it’s just about to close. And anyway, again, his prices went up when it was.

Speaker 1: What’s your favorite Spanish word? That’s my last question for you. Phenomenal. OK, well, phenomenal, which means almost the same thing in English. I know they’re not really safe for them.

Speaker 4: But you know, the time don’t they?

Speaker 3: We are you. All the time. Phenomenal.

Speaker 2: Well, it’s been really phenomenal.

Speaker 1: Yes, phenomenal. Thank you for coming on the podcast. And if anyone wants to see Kevin talk and put some questions to him themselves, they can come to Secret Kingdom’s bookshop on November 21st at 8 p.m. What day is that? Is it a Friday or something?

It’s a Friday, yeah. OK, all right. Well, thank you very much, Kevin. Oh, thank you. Thank you again. OK, bye bye.