Madrid holds a distinction that may surprise many visitors wandering through its grand boulevards and royal palaces: it’s the only European capital city founded by a Muslim ruler. Yet this fundamental fact about Spain’s capital often remains largely hidden from public view, buried not just in time but quite literally underground in car parks and behind locked doors.

The Birth of Mayrit

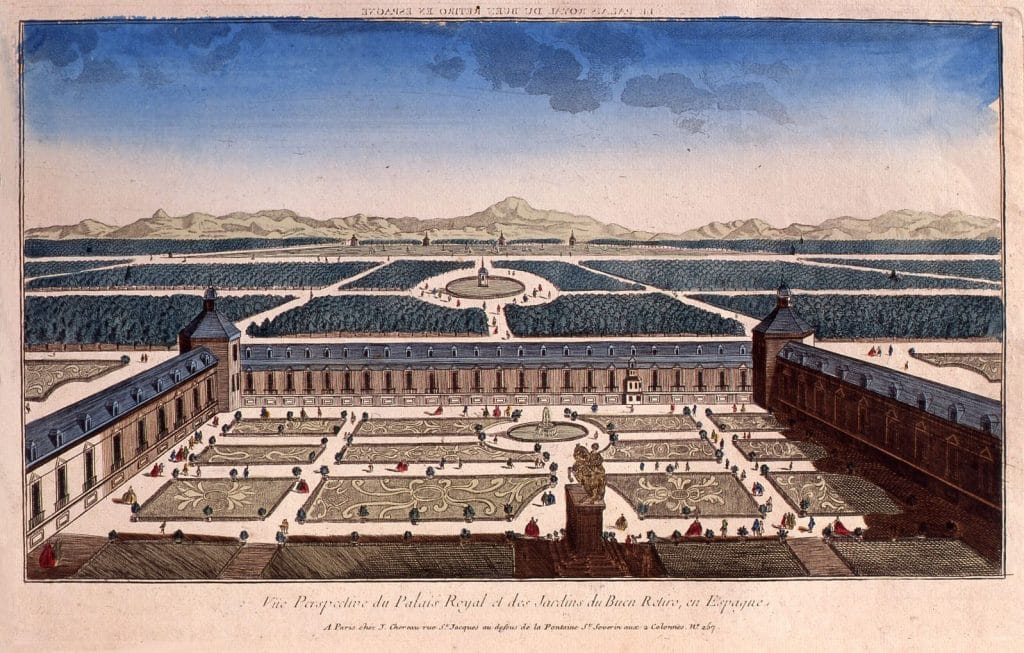

In the 9th century, when Madrid was nothing more than countryside dotted with waterways, Emir Mohammed I of Cordoba made a strategic decision. Facing Christian uprisings in the important city of Toledo, the Muslim ruler established a line of defensive watchtowers, with one positioned on a hill where Madrid’s Royal Palace now stands.

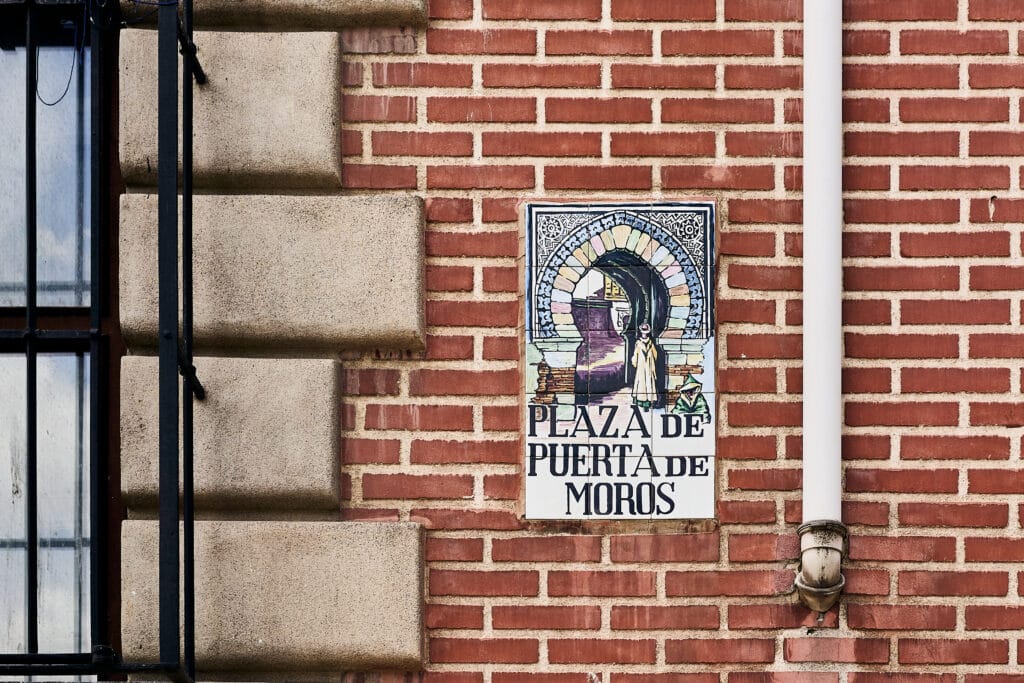

The settlement was called “Mayrit,” meaning “place of waterways.” The name referenced the network of underground streams and channels that made this location particularly valuable—water sources that would prove crucial as the small fortress gradually expanded into a thriving medina.

This wasn’t a grand city from the beginning. Mayrit started as a practical fortification, designed to sound the alarm when Christian forces approached from the north, preventing them from linking up with rebels in Toledo. But the strategic position and abundant water supply allowed the settlement to flourish over the following centuries.

Archaeological Evidence Hidden in Plain Sight

The Muslim origins of Madrid aren’t merely academic theory—they’re backed by substantial archaeological evidence uncovered during modern construction projects. In the 1990s, excavations beneath the Plaza de Oriente revealed a treasure trove of Islamic artefacts: sophisticated ceramics with distinctive glazes that made clay vessels reusable (an advancement over Roman pottery), storage silos, and countless everyday objects from the medieval Islamic settlement.

Perhaps most remarkably, an 11th-century watchtower from the original fortress remains, accessible through the Plaza de Oriente car park. Yet this significant piece of Madrid’s founding history lacks any signposting whatsoever. Visitors stumble upon it by accident, if at all. Even worse, a small display of finds set up in the Plaza de Ramales car park entrance is only accessible to key holders or intrepid people waiting outside the door for someone to come out and let them in.

The situation becomes even more puzzling when you discover that the majority of these archaeological finds were shipped off to a museum in Alcalá de Henares—Cervantes’ birthplace and a city with Roman origins. In contrast, the Museo de San Isidro, a nearby museum dedicated to the origins of Madrid, wound up with only a few items for its display cases.

The Mosque Beneath the Cathedral

Evidence suggests that the original mosque of Mayrit lies beneath the remains of what was the church of Santa María de la Almudena on Calle Mayor. When Alfonso VI of León and Castile conquered Madrid around 1083, he would likely have followed his standard practice of converting mosques into churches—a symbolic assertion of Christian dominance that he implemented throughout his territories.

Yet even this significant site remains unmarked and unexplained. Glass panels reveal the archaeological remains, but they’re covered in dust and provide no context about what visitors are seeing. The connection to Madrid’s Islamic past goes unmentioned.

Why the Silence?

The reluctance to properly acknowledge and display Madrid’s Muslim heritage appears tied to contemporary politics rather than historical uncertainty. The evidence for Islamic origins is overwhelming and accepted by mainstream academics, but certain political factions prefer alternative narratives.

Some have attempted to promote theories of Roman or Visigoth origins for Madrid, despite the lack of supporting evidence. While Roman artefacts exist in the broader region—visible at the Museum of San Isidro—no Roman settlement existed at Madrid’s actual location. The Visigoth theory appears even more recently constructed—more on that in the next episode of my podcast!

Traces That Remain

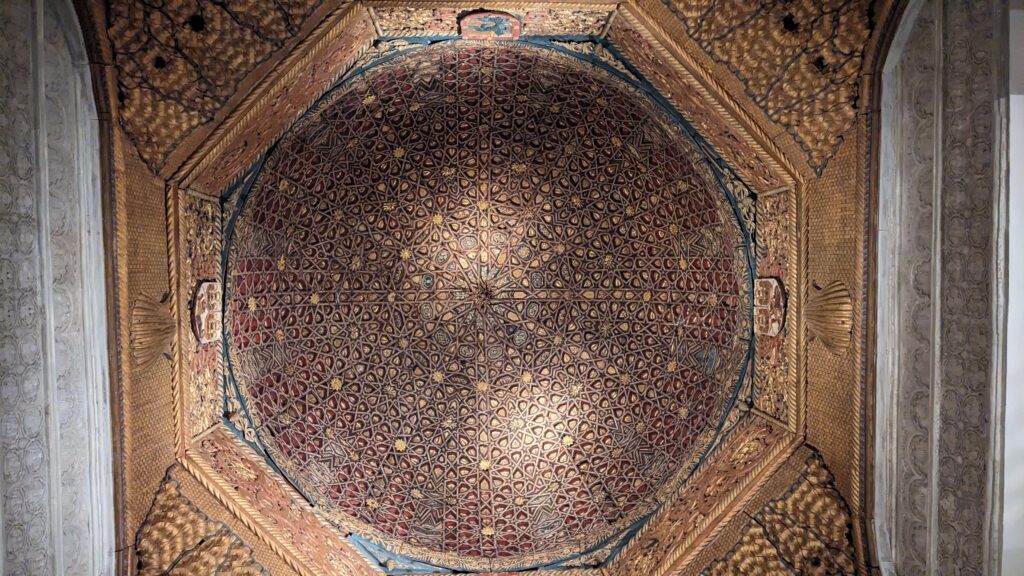

For those determined to glimpse Madrid’s Islamic heritage, a few traces survive above ground. The Church of San Nicolás Real, built in the 12th century by Muslim artisans working for Christian rulers, features distinctive horseshoe arches and a square tower characteristic of Islamic architectural traditions. Though often mistaken for a converted mosque, it was actually constructed as a church using Islamic design elements that Christians initially admired and adopted.

The church is often closed and is a little underwhelming inside. So if you’re interested in this artistic heritage, head for the Museo Arqueológico Nacional, which houses stunning examples of Mudéjar ceilings and Islamic decorative arts from across Spain. The medieval walls, just below the Catedral de la Almudena, are hidden in a garden that’s closed on weekdays and poorly signposted.

Uncovering the Hidden City

For travellers intrigued by this hidden history, there’s now a way to explore Madrid’s medieval Islamic heritage firsthand. My Medieval Madrid audio tour on VoiceMap guides you through the city’s founding story, from the original watchtower site to what became the city’s Morería when the Christians took over.

This self-guided walking tour reveals the locations mentioned in this post while providing the historical context often missing from official signage. You’ll discover not just the car park watchtower and cathedral remains, but also learn to read the architectural clues scattered throughout the old city that reveal Madrid’s Islamic origins.

The tour takes you beyond the obvious tourist sites to uncover the genuine medieval city that preceded the grand imperial capital. While Madrid’s city council may be reluctant to fully embrace its Muslim heritage, the Medieval Madrid tour ensures visitors can access this fascinating chapter of European history.

Available through VoiceMap, this audio experience transforms a simple walk through central Madrid into a journey back to the 9th century, when Mayrit was just a strategic watchtower defending the approaches to Toledo. The history is there, substantial and fascinating—you just need to know where to look for it.